Taliesin: The Forging of Style

Hillside Studio

On a sunny morning in early October, as the leaves changed colors in Southern Wisconsin, I entered Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hillside Studio. Our guide had been speaking up to that point and though I was listening attentively, his words started to fade and my attention began to drift. Suddenly, I was smiling from ear to ear. Rays of autumn sunshine pierced through the windows, casting a golden glow across the room. My gaze wandered to the prairie beyond. My mind grew silent as light masked my face with a warm, powerful energy. Almost as if Wright’s words were echoing inside: “Love of an idea is the love of God.” I snapped out of it as the guide, coincidentally, pointed me to an etched Bible verse in the wooden rafters above. It read:

“But those who wait on the LORD Shall renew their strength; They shall mount up with wings like eagles, They shall run and not be weary, They shall walk and not faint.”

This moment at Taliesin was more than making the four-hour drive from Chicago to witness genius. It was about experiencing the “Prairie Style” and deepening my understanding of his organic architecture principles. Though I’ve already taken several tours of his studio in Oak Park and the Robie House in Hyde Park, seeing the theme of horizontal lines in action, I felt more research was needed about the story behind the creation of his unique vision. Why? Because my startup is crafting its own style in educational design, which will undoubtedly include the creation of spaces. So, as a first time founder I embarked to uncover the power behind Wright’s forging of his Prairie Style. Perhaps I too will forge an effective style, one worthy of belonging to the American educational landscape.

Divine light entering.

The masculine.

The feminine.

The etched verse from Isaiah 40:31

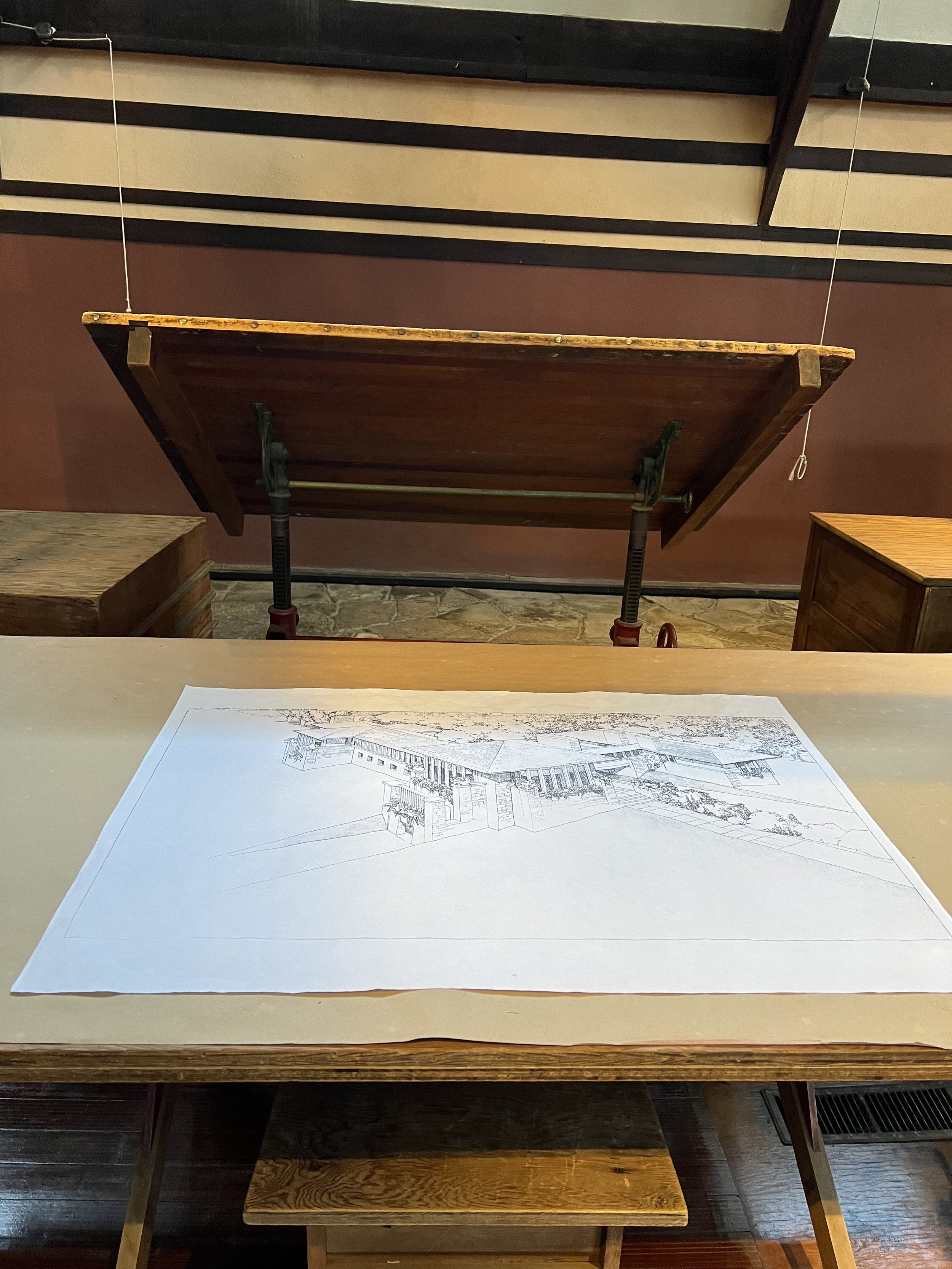

Eventually, we reached the drafting room and soaked in the atmosphere of creativity. We saw where he and his apprentices toiled away with blueprints and innovative designs. At the opposite end was an enormous fireplace with a fat, orb-like kettle. One could not help but wonder of all the late nights and early mornings spent honing the methods and secrets of their craft. When asked to describe the estate, Wright explained,

“Taliesin is an instance of going back, to the soil, and really developing it, and trying to make something beautiful of it. [The name] means ‘shining brow’, built on the edge of the hill, not on top of the hill, if you build on top of the hill you lose the hill.”

There is definitely a common sense evident in the designs and functionality of Wright’s approach along with a strong sense of vitality. He designed 1,114 architectural works of all kinds; 532 of which were actualized. However, my interpretation is that at the heart of his style lies what I would describe as: relentless determination. I will explain and elaborate a bit later, first I must share how I eerily came to this realization.

It happened as we finished boarding the shuttle and left Hillside Studio en route to Taliesin, the home where Wright lived. The joyous feeling of being surrounded by breathtaking beauty was awesome. It was an ineffable high and the guide was continuing to recount fun details about other structures such as Tan-y-Deri and the Midway Barn. But then, abruptly I was struck with a deep sadness and felt a strong, dark energy. It was an undeniable force that completely overwhelmed me. Again, I could no longer hear the guide’s words as I was disturbed by the unexplainable, seemingly random, sensation I was experiencing inside. “Get a grip!” I thought to myself. “What the hell is going on with me?” The guide even gave me a concerned look as we arrived at the entrance.

I wiped my sweaty palms and tried to shrug it off. Once inside, I did my best to put the strange feeling behind me. Except, upon entering the dining room our guide asked us to take seats in the various benches and chairs around him, as if he had something important to share. We all just knew something was coming. But I had absolutely no clue and was completely blindsided by what he was about to say.

Drafting room.

Drafting table with sketch.

Fireplace and kettle.

Cool!

The guide shared with us that in August of 1914 a great tragedy took place at the Taliesin estate. While Wright was out of town, one of his staff workers, Julian Carlton set a portion of the house on fire and killed seven people. Notably, Martha “Mamah” Borthwick (mistress of Frank Lloyd Wright) and her children, Martha, 9, and John, 12. Carlton used an axe to murder his victims. It was a gruesome, bloody scene of arson and death. This is where I interpret the real beginning of the forging of what we’ve come to know as the “Prairie Style”. Because although this horrific catastrophe naturally sent Frank Lloyd Wright into grief and despair, he immediately vowed to rebuild the totaled portion of Taliesin, and build it even better than before! Relentless determination. In his autobiography, he wrote:

“Taliesin should live to show something more for its mortal sacrifice than a charred and terrible ruin on a lonely hillside in the beloved Valley.”

Wright finally accomplished this in 1924 with Taliesin II. However, the following year another fire, this time caused by a lightning storm, would destroy yet another part of Taliesin! According to taliesingpreservation.orgWright wrote, “Taliesin lived wherever I stood! A figure crept forward from out the shadows to say this to me… [T]aught by the building of Taliesin I and II, I made forty sheets of pencil studies for the building of Taliesin III…. Taliesin’s radiant brow … should come forth and shine again with a serenity unknown before.” In 1925 despite being in debt, Frank Lloyd Wright managed to pull off rebuilding Taliesin for the third and final time. Guided by the even more powerful “Prairie Style”, forged by flames of death, depression, divorce, and debt — it reemerged with its relentless determination — everlasting, elevated, embracing, and extravagant.

Energy from Another Dimension

The first thing that came to my mind after hearing of the seven murders was the sad, macabre force that I felt in the shuttle arriving to Taliesin. It instantly made sense. (I wasn’t tweaking after all.) If I’m being honest, this wasn’t the first time I’ve had such an odd, frighteningly real, vibe about life, death and energy based on being at a location or physical space. Where did that weird undeniable energy come from? Another dimension? I don’t know. And funny enough, this is where I draw more parallels between Frank Lloyd Wright and his Prairie Style and myself and the style I am forging with Learning Producers, Inc. An interviewer once asked Wright, “What do you consider is your most satisfactory achievement?” He responded, “The next one, of course. The next building I build.” The interviewer continued to press, asking him, “What is that?” Wright answered, “I don’t know. I’m not sure but whatever it is, that will be it.”

I, too, don’t know. I don’t know how to explain our experiences. I don’t know what lies ahead. The unknown baffles me as much as it does you. Yet, like Wright, I know what we build in the future will be our best work. In the same interview he had described Taliesin as follows, “[Having] low hills, protruding rock ledgers. The site determined the features and character of the house…I’d like to have architecture appropriate to the Declaration of Independence, to the centerline of our freedom. Architecture that belonged where you see it standing. And was a grace to the landscape instead of a disgrace.”

Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright’s home.

Sandstone and other local materials were used from nearby quarries.

I ran to the edge of the balcony and screamed, “I’m king of the world.” (Just kidding.)

The Unknown & Forging Ahead

In essence, we feel the same way about forging our design style in America’s educational landscape. We will challenge the boxy, claustrophobic schools of today with their cinderblock walls and bad fluorescent lighting. The corny bulletin boards and tacky decor of hallways and classrooms is too conventional. It’s time for the unconventional. As Wright the man himself said, “We must come back, to the soil, and try to make something beautiful out of it.” Hybrid learning, as in indoor spaces that seamlessly blend with nature and allow outdoor adventures. Less boxes more geodesic domes and greenhouses, and workshops. No more having one educator trapped in a room with 30 scholars; instead, groups of educators working with groups of scholars in a decentralized system. And of course with AI accelerating, we must exploit opportunities for home learning; all this makes for pedagogical wabi sabi. That is, the Japanese concept of embracing the beauty in imperfection, cycles of growth and decay. It won’t be perfect, but we will build towards our aesthetic ideals.

As a matter of fact, after Taliesin burned the second time, Wright instead of being devastated that his sculptures from Japan were charred and fragmented, he used those pieces to rebuild his home the third time. Wabi-sabi in action.

Bullying & conflicts can be opportunities; have scholars put on boxing gloves, head gear, mouth guard & spar!

Indoor and outdoor hybrid learning is the future, let’s build it together!

Inspired by Taliesin and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie Style we’re back in the drafting studio, so to speak. Sketching the protruding rock ledgers of well-being, the modern architecture of free speech, and the grace of risk, forged in every great adventure. When you see it, you will know it belongs where it stands.